what's the point of passing on useless languages?

aka: local man cannot decide on what he thinks of the value of language preservation.

When you drive up the Sea-to-Sky Highway from Vancouver to Whistler, you'll notice something that wasn't there when I was born: bilingual signs featuring English and Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, the language of the Squamish First Nations who have been stewards of the area for millennia. These signs are unfunctional for myself and the vast majority of the population. Even amongst the Squamish people, most are not fluent in their traditional language due to centuries of cultural genocide and assimilation (see: the Indian Residential School System).

The first time I saw them at the age of maybe, nine, a question hit me: what's the point of preserving a language that has no practical "use" in a society obsessed with efficiency? Why devote resources to languages spoken by shrinking populations when we could all just speak English and be done with it?

Eight years later, I now know the on-paper, PR answer to this question: it's part of our reconciliation efforts to mend relations with Indigenous peoples by recognizing and celebrating their vulnerable languages. But I can't help but look at those signs and see a reminder of my own fears: that perhaps one day I will not be able to pass on my family's language to the next generation. I also can't help but also ask if these well-intentioned gestures are more about assuaging collective guilt than creating actual utility

what the hak is hakka?

My Malaysian grandmother's voice changes when she speaks Hokkien. It rises from somewhere deeper in her chest, carries a melodic quality that her Cantonese lacks. Her hands move differently with more expansive gestures, like she's physically grasping at words that exist in one language but not another.

When she switches to Hakka to argue with my grandfather, her entire face transforms. I can't understand a word, but I can read every emotion. And when she turns to me, her features soften as she switches to English in that not quite seamless way--what some call "Engrish". "You want more food, lah? You're too skinny!" Her accent is sometimes a wee bit thick, but her love needs no translation.

I nod and smile, responding in the only language I truly know. My Cantonese is embarrassing--baby talk that makes my cousins in Hong Kong snicker behind their hands. Have you ever tried to learn Cantonese? Nine different tones can completely change the meaning of otherwise identical words. Say "ma" with the wrong pitch and you've just called someone's mother a horse. Even native Mandarin speakers struggle with it.

I am what linguists politely call "heritage language incomplete." What my relatives less politely call "banana"; yellow on the outside, white on the inside.

all-canadian boy.

Growing up in suburban Canada, I never realized what a miracle my grandparents are. Between them, they speak languages that emerged from different millennia, different dynasties, different worlds. Languages that barely anyone in the Asian diaspora of the West are fluent in. Languages with writing systems so complex they take years longer to master than alphabetic ones. The average Chinese student spends thousands of additional hours just learning to read and write compared to English-speaking peers.

Every two weeks, a language dies. When the last fluent speaker exhales their final breath, thousands of years of human experience vanish. Not just words and grammar rules--entire ways of seeing reality.

Did you know that in Cantonese, there are specific words to describe the precise texture of foods that English reduces to "crispy" or "chewy"? That Hokkien contains emotional concepts so specific they can't be translated directly into English? That Malaysian Hakka preserves ancient Chinese features and lexicon that have been extinct in mainland China's Mandarin for decades?

When these languages go, we lose cognitive frameworks, cultural memories, among other things. The legacy of countless generations who survived plagues, wars, famines, colonization, and still found reasons to develop words for specific types of joy. But we also gain something more valuable: efficiency, connectivity, a shared global experience. There's a reason English has become the lingua franca of commerce, technology, and international relations. It's not just colonial legacy--it's admittedly also pragmatic reality. Many Asian languages present formidable barriers to outsiders, and even insiders. Mandarin has over 50,000 characters, though you "only" need 3,000 to read a newspaper. Compared to English's 26 letters, the learning curve is a mountain, not a hill.

Here's the irony: my grandparents survived wars, poverty, and displacement to make sure I could grow up safe and well in Canada--and in doing so, created the perfect conditions for our family languages to die with them. The immigration bargain is brutal. The pressure to assimilate is relentless. My parents, watching their own parents struggle with broken English, made a choice: English first, heritage later. Except "later" never came.

We are desperate to assimilate, as if it will finally earn us acceptance. I watch Asian-Canadians perform whiteness like our lives depend on it. Parents thinking they're doing their kids a favor by prioritizing the dominant language. Changing names, ridiculing accents, distancing ourselves from "fresh off the boat" relatives. For years in elementary school, myself and all of the "ethnic" kids were placed in ESL classes--separated from our white classmates--despite the fact that we were all perfectly fluent in English.

Those classes taught me nothing particularly new; except that differences must be punished.

the politics of language erasure.

Languages don't just die--they're killed. Often deliberately and with the full force of state power.

The Chinese Cultural Revolution wasn't content to destroy temples. It had to simplify the written language itself, stripping away the complex characters that had evolved over thousands of years. Traditional Chinese characters aren't just pretty (and hard to write), they're also repositories of cultural memory. The simplified versions introduced by the government might be more efficient, but they sever connections to etymology, to poetry, to the visual logic that links concepts across millennia.

See the following example--the traditional Chinese word for "love".

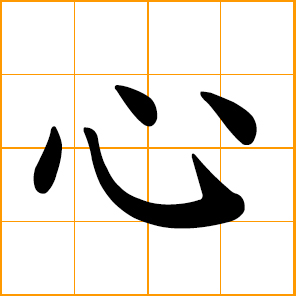

Take a look at this particular radical within it; meaning "heart".

You cannot have "love" without putting your "heart" into it. My mother says that simplified Chinese strips the heart of our ancestral Chinese characters.

This language erasure has happened everywhere. Indigenous languages across North America were beaten out of children in residential schools. European colonial powers criminalized local languages across Africa and Asia. The justification is always the same: efficiency, modernization, progress--and hey, regardless of the ethics of these methods, it's worked. I can talk to people from Nunavut to Australia to Nigeria and understand them without a language barrier.

There's undeniable truth to the efficiency argument. A world with fewer linguistic barriers is one where ideas, innovations, and information flow freely across borders. One can argue that standardization creates legitimate benefits that sentimentality about language often ignores. Would we really prefer a world where medical breakthroughs remain isolated in linguistic silos? Where scientific collaboration requires armies of translators?

But returning to the main point, why do I care in the first place? I can't even read or write Traditional Chinese.

the broken chain.

My aunt cornered me (verbally) recently. "Your children won't speak Cantonese," she said. Not a question--a statement of fact. I started to protest, but who am I kidding? I can barely order dim sum without embarrassing myself. How am I supposed to teach my hypothetical children a language I don't speak?

This is what linguists call "three-generation language shift." The immigrants speak their native tongue. Their children understand it but respond in English. The grandchildren lose it entirely. A bloodline's linguistic extinction event compressed into less than a century.

The guilt is suffocating sometimes. I'm the broken link in a chain that stretches back thousands of years. My ancestors kept these languages alive while literally fighting for their survival--and I let them die because I was too busy trying to fit in and take the easy way out.

But perhaps, that's okay too. Perhaps this is just cultural natural selection at work. Languages, like species, adapt or die according to their fitness for the environment. English provides something my ancestral languages can't: universal connectivity without requiring a decade of intensive study. And isn't connection the whole point of language in the first place?

the point.

So what is the point? Why preserve a language that most people will never speak, that seems to have no "practical value" in our globalized economy? When you drive up that Sea-to-Sky Highway and see those Sḵwx̱wú7mesh signs alongside English, different people will draw different conclusions. For some Squamish elders, especially those who survived the Indian Residential School System, seeing their ancestral words on official signage may fill them with joy and pride for their language finally being celebrated. For practical-minded administrators, it might be primarily a tourism asset or political goodwill. For linguists, it's data preservation. For many drivers, it's simply background noise they barely notice. Others may question the allocation of resources to maintain languages with dwindling speaker populations

There's no objective answer here. The question forces us to examine what we value and why.

I find myself similarly conflicted about my family's languages. When my grandmother speaks Hokkien, Malay, or Cantonese, I experience both connection and disconnect; drawn to something that feels like it should be mine, yet isn't. My attempts to learn feel simultaneously like obligation, curiosity, guilt, and genuine interest.

Maybe that's the nature of heritage--not something we can objectively measure in value, but something each generation must evaluate for itself. Some will choose preservation at all costs. Others will adapt and integrate. Most of us will navigate some middle path, carrying forward certain elements while letting others go.

A graduate from my high school (hi Eddie) once argued in a similar essay about his Asian heritage that he wants to preserve his language so that he can preserve himself. Because to him, heritage is what makes us... us. I (kindly) call bullshit. Heritage is part of our story, not the whole story. It's an influence, not a destiny. The languages my grandparents speak shaped them, but their absence in my life hasn't left me empty. It has created space for other influences, other perspectives, other ways of being.

I need to forge my own path, with or without my ancestral languages. Yes, there are doors closed to me because I can't speak Cantonese, Malaysian, etc. fluently. But there are other doors open precisely because I grew up with English as my primary language, with a foot in multiple worlds, with the ability to question which traditions to keep and which to leave behind. And most importantly, with the ability to express things like "straight up jorking it to hot MILFs in the stripped club".

I don't know if my future children will speak any of my family's languages. I don't know if they'll feel the absence of these languages as a loss or simply as a neutral fact of their existence. I don't know if the emotional weight I attach to these languages is inherent or simply a product of my particular circumstances and generation. I don't know if I even care.

What I do know is that when a relative speaks to me in a mixture of Cantonese and broken English, and I respond in my English with occasional Cantonese phrases thrown in, we're both trying to bridge a gap. Whether that gap should have existed in the first place, or whether it's simply the natural evolution of human culture, isn't a question with a universal answer.

Maybe we need to consider that it's more practical to look forward than to romanticize what we've left behind.